"My grandchildren will play with me. I am clean. I can practice my faith. I can live."

Kabul, Afghanistan - Within the gates of Malalai hospital hundreds of women, children and anxious men sit in the few sunny areas of the courtyard, bouncing sick babies on their laps, waiting. Inside the female-staffed maternity hospital, the halls resonate with the moans of women in labor while they share beds in crowded rooms humid with the stress of new birth.

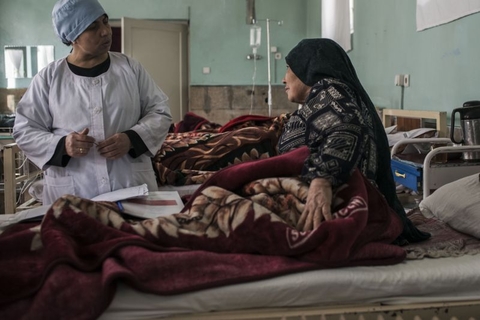

Further down a maze of hallways, hidden at the end, is a silent space where seven women sleep under heavy blankets. Exhausted and worn as if ending months of weary travel, these women are recovering from fistula surgery, and more importantly, from years of exclusion from society. Because of the constant smell of urine that caused them heartbreak and shame, they were shunned from everyday life, unseen in daily life, and abandoned by their husbands.

Obstetric fistula is a devastating injury acquired during prolonged or obstructed labor without timely access to emergency obstetric care, resulting in a hole between the vagina and bladder or rectum, which leaves women leaking urine or feces. The fistula ward in the Malalai Maternity Hospital, supported by UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund and Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health, is one of few places in Afghanistan women can receive free emergency obstetric care and surgeries by trained female surgeons.

Fistula surgery is the solution to a problem that often seems unapproachable in Afghanistan. In some ways, women with fistula issues are considered the lucky ones, surviving the high maternal mortality rate that haunts Afghanistan; though none of them would think of themselves as lucky. A lack of maternal care and education, malnutrition, child marriage, remote villages on rarely traveled roads, society’s powerless role for women, not to mention ever-raging war, all stack up against women who suffer this problem.

Noorjahan, 67, lived with fistula for 49 years until her recent surgery. During those years she hid in one room, rarely leaving, sewing to make a living. Every morning, afternoon and evening she cleaned her soaked mattress and searched for plastic bags that she tied around her like diapers.

To find the fistula ward, Noorjahan traveled from far away to reach Kabul, a difficult task for an illiterate woman with obstetric fistula, hanging on a rumor she had heard about the existence of doctors who could help her. For four days she wandered the streets of Kabul before finally finding Malalai Maternity Hospital and the fistula ward inside.

Now, days after surgery, Noorjahan smiles.

“I can die now. My grandchildren will play with me. I am clean. I can practice my faith. I can live,” she says with a laugh that ends only because of the pain leftover from surgery.

While she drinks tea, delicately rearranging herself in her bed, she is visited by former patients who now are attempting normal lives and have returned to the ward for a check-up. They interact like war veterans, understanding the torment of their lives without having to speak of it, checking in with each other in the recovery room, and sharing each other’s silent tears after nightmares about the life before.

One such fistula veteran is Guldesta. She married at the age of 12 and had a son at 13 in the distant region of Pul-e Khumri. She had two daughters, then several miscarriages that led to an obstetric fistula. She lived with the injury for many years until her surgery at Malalai Hospital.

“People have told me not to take my daughter or daughter in law to a hospital when she is about to give birth, but I have never listened to them. I have seen so many problems and difficulties of fistula. I wasn’t able to sit a minute with my guests because I had a bad condition. I was sitting alone for days and nights,” she said.

Now, she is a mother-in-law with a grandchild.

Guldesta’s is a rarity in her community. Living in a three-room home without running water that she shares with over 15 people, she lives in a community where poverty is rampant and education is scarce. But through her own experiences with fistula and the doctors who helped her, she has made it her duty to educate others, starting with her own family.

“My daughter is too young to marry now, but I will see what the future brings us. My older daughter is married to a man in Jabulsaraj (a district in Parwan) and there are not many hospitals around. She is here now and I will take her to Malalai Hospital whenever she is about to give birth.”

Doctors who work with UNFPA and the Ministry of Public Health say that lack of education is at the center of the problem. Compared to the amount of women who suffer from an obstetric fistula in Afghanistan, very few have actually made it to Malalai Hospital for care.

UNFPA attempts to address the issue by supporting training of female midwives and doctors who can help women with preventing and recovering from this injury as well as educating men and women on the problems of child marriage.

“Women wouldn’t be allowed to come to the hospital if there were male doctors,” says Dr. Nazifa Hamrah, 51, a fistula surgeon. “All of my colleagues are women, so we are very comfortable and can focus on our work.”

The training of midwives to work is central to preventing fistula. UNFPA supports training of midwives who are selected from their rural communities through a process involving families, shuras and elders to make it a community decision to educate women as midwives, showing its importance to all involved. The process also ensures that future midwives return to serve the community once they have completed their education in the Family Health Houses that the community have built.

In these regions finding girls who have completed a 10th grade education is often difficult. An 8th grade education is required. But, through training, these midwives have become the heroes to women in their region, one doctor said.

Sina Alizada, 41, trained as a midwife in the mountains of Bamiyan. House calls were made by horse, the roads too treacherous for cars or motorcycles.

There are many issues related to fistula problems in Afghanistan that need more attention, explained UNFPA Representative, Bannet Ndyanabangi. “The isolation and stigma of the recovering women is not over even after medical treatment. The survivors need help to start making a living and for reintegration into their communities for a life of dignity and hope.”

- Andrea Bruce